-

Environment-Consumer Willingness to Pay for Fair TradeCoffee: A Chinese Case Study2016-05-24

Tag:Environment

Journal of Agricultural and Applied Economics, 44,1(February 2012):21–34

2012 Southern Agricultural Economics Association

Environment-Consumer Willingness to Pay for Fair TradeCoffee: A Chinese Case Study

Shang-Ho Yang, Wuyang Hu, Malvern Mupandawana, and Yun Liu

Coffee consumption in China has seen a significant rise in recent years. This study seeks to explore the determinants of coffee consumption in China with a specific focus on fair trade coffee. In a survey of 564 respondents in Wuhan City, consumers' willingness to pay (WTP) for fair trade labeled coffee was measured. This study uses an interval regression to investigate individual demographic and consumption characteristic impacts on WTP. Results show that on average, consumers were willing to pay 22% more for a medium cup of fair trade coffee compared with traditional coffee. In addition, other variables that indicated a higher WTP included female consumers, consumers who made their own coffee, and consumers who planned to consume more coffee in the following year.Key Words:China, fair trade coffee, interval regression, willingness to payJEL Classifications:D12, Q13

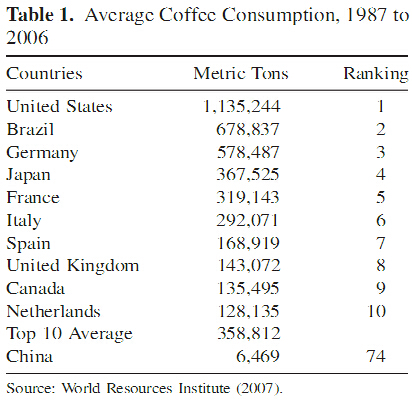

According to the coffee consumption data fromthe World Resources Institute from 1987–2006(World Resources Institute, 2007), the annualaverage total consumption of coffee beans inChina totaled 6,469 metric tons, ranking 74th inthe world. For the top 10 countries, the annualaverage total consumption of coffee beans to-taled 358,812 metric tons from 1987–2006(Table 1). Thus, when compared with the world’smajor coffee markets, the cof fee market in China may appear trivial. However, following rapideconomic growth, China has the potential to be-come a major cof fee market in the future ( BeijingZeefer Consulting Ltd., 2009). This has impor-tant implications to cof fee producers, marketers,and retailers worldwide.Due to historical dietary habits and culturaldifferences, coffee in China is consumed muchless than in western countries, such as the UnitedStates, Canada, and European countries. Never-theless, China has positiv ely increased its coffeeimports from the United States over the last twodecades (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Foreign Agricultural Service, 2010). Does thismean that Chinese consumers are graduallychanging their bev er ag e preferences? What otherfactors may affect their consumption? This studycontributes to the literature as one of the first toexamine Chinese cof fee consumers and their pur-chasing behaviors.In regards to Chinese coffee consumption,at least 70% of cof fee was consumed in the formof instant coffee—the most popular form forcoffee at the retail level (FriedlNet, 2003).

Roasted coffee sold in processed or prepack-aged form is still rare. However, this trend isstarting to change. For example, the Seattle basedcoffee company Starbucks Co. faced reducedprofits in the United States and several othermarkets in 2008 and 2009, but saw no declinein its China business (Allison, 2009). Further-more, the number of Starbucks coffee shops inChina is expected to grow to over 700 storeswithin the next 10 years (Allison, 2009). Mostof these stores sell br ewed coffee. With thestrong economic growth in China, consumersdo ha ve more options and are more open to sam-ple beverages not traditionally consumed. In thisgrowing market for coffee in China, consumerattitudes are the key to compare factors deter -mining consumers’ purchasing behavior in Chinato other major coffee markets.Fair trade coffee may have a niche market inChina if consumers are aware of and concernedthat coffee producers may not always receive a‘‘fair price’’ for their coffee beans. Thus, buyingcoffee that bears the ‘‘Fair Trade’’ label is a wayto help coffee producers. To explore the atti-tudes of Chinese consumers regarding fair tradecoffee, we evaluate through their reported will-ingness to pay (WTP). The objectives of thestudy are to 1) ascertain Chinese consumers’WTP for fair trade coffee; 2) examine the de-terminants of WTP for fair trade coffee, (i.e.,outline the specific demand-related characteris-tics of each consumer group); and 3) add China to the country analyses of coffee consumptionbehavior in the literature that is often based onU.S., Canadian, and European data. It is of in-terest to show how Chinese coffee consumptionmay differ from that seen in these countries andhence, how the results of this study may differfrom previous studies. The result of this researchis crucial for coffee traders and marketers toconstruct their marketing and promotion strate-gies in sync with consumer demand.In China, coffee is often not seen as an or-dinary beverage. In the 1980s, coffee drinkerswere rare and coffee was usually treated as high-priced imported gift items exchanged more forits token value (i.e., as an expensive gift) ratherthan actual consumption value. Today, morepeople in China may consume coffee for thesame reasons as in most western countries. Thesedifferent reasons represent diffe rent attributedimensions when a customer purchases coffee,such as brand-orientated, flavor -orientated, ethical-orientated, and price-orientated. Since the be-havior of purchasing coffee entails many attributedimensions and product labeling often conveysinformation that may not be directly or easilyobserved by consumers (Caswell and Padberg,1992), it is necessary to understand how cus-tomers choose coffee and on what informationthey base their choices. Furthermore, infor-mation such as social or environmental benefitsmay affect coffee consumption decisions as well.Fair trade labeling of cof fee products caters tothe behavior of ethical consumption. Therefore,this study focuses on how Chinese consumersevaluate fair trade coffee in terms of their will-ingness to pay.

Literature Review

Fair trade is an organized social movement andmarket-based approach to help producers in de-veloping countries obtain better trading condi-tions and promote sustainability. Among fairtrade products, coffee has the largest sales vol-ume and the longest history dating back to 1989(James, 2000). According to the broad conceptof fair trade from Pelsmacker et al. (2005), thefair trade label can be expressed as an alterna-tive approach to aim at sustainable developmentof excluded and/or disadvantaged producers; within the narrow sense of fair trade, it is bestknown as fair prices for the products of farmersin developing countries. Hence, the main featureof the fair trade movement is a product labelaimed at informing consumers that growers re-ceiv e a ‘‘fair price’’ for their product.

Coffee may be seen as a western-style bev-erage to Chinese consumers. In China, western-style foods are often symbols of modernizationof food consumption and it is this idea thattriggered the fast expansion of western-styleconvenience foods in China (Curtis et al., 2007).The McDonalds fast food chain is a successfulexample of western-style convenience foods en-tering the Chinese market. Watson (1997) indi-cates that McDonalds could not have succeededwithout appealing to the younger generation ofconsumers who are eager to reach out to a dif-ferent culture. There is scant literature on con-sumer coffee preferences or fair trade labelingin China. However, while China is opening itsdoors to the world, it is reasonable to anticipatethat western-style tastes and preferences willemerge for coffee, especially among its youngercitizens.

Fair Trade Labeling Related to EthicalConsumption

What is the motivation for ethical consumption?Doane (2001) described that ethical consump-tion as a purchasing behavior based on ethicalconcerns, such as human rights, labor condi-tions, animal well-being, and the environment.According to Pelsmacker et al. (2005), ethicalconsumers feel responsible toward society andexpress these feelings via their purchasing be-havior. Hence, if consumers understand whatfair trade labeling is, then they may feel re-sponsible for this cause and be willing to paypremiums above standard prices. In essence, fairtrade is a concept for coffee consumers thatbuying fair trade coffee helps growers in de-veloping countries. Like other similar labelingstrategies, such as organic or local product ionlabels (Bernard and Bernard, 2009; Darby et al.,2008), consumers who have ethical concerns mayhave a higher willingness to pay.Studies such as Greenwald and Banaji (1995)find that people are not always willing to report their attitudes accurately, especially in the caseof socially sensitive issues such as ethical con-sumption behavior. This implies that the exis-tence of the attitude-behavior gap could biasour WTP results. Shaw and Clarke (1999) usean extended Ajzen’s theory of planned behaviorto explain belief formation and fair trade prod-uct buying intentions. Their results show that both behavioral control (i.e., perceived behav-ioral control and control-related elements of at-titude) and internal reflection (i.e., subjectivenorms, ethical obligation, self-identity, and atti-tudes toward fair trade) have about ‘‘equal weight’’in explaining intention to buy fair trade products.

However, beliefs may play a significant rolein actual behavior (Shaw and Clarke, 1999).The gap between attitude and behavior is oftenreferred to as the behavior intention, which canbe controlled by influencing factors such as price,availability, ethical issues, convenience, infor-mation, and time. There is no guarantee that theresults of the WTP estimation eliminate the gapbetween attitude and behavior. However, Shawand Clarke showed that the attitude-behaviorgap could be controlled or reduced if the eco-nomic trade-off principles are set up appropriately.In this study, we assume the attit ude-behaviorgap is constant through the process of our datacollection.

Previous Studies Regarding Consumer WTP forFair Trade Coffee

By the end of 2007, fair trade certified productswere available in more than 60 countries. In2007, worldwide consumers spent over 2.3 bil-lion Euros for fair trade certified goods (WorldFair Trade Organization, 2009). Recent studieshave investigated fair trade coffee in countriessuch as Canada, the United States, and someEuropean countries (Arnot et al., 2006; Basuand Hicks, 2008; Catturani et al., 2008; Cranfieldet al., 2010; Galarraga and Markandya, 2004;McCluskey and Loureiro, 2003; Pelsmackeret al., 2005; Wolf and Romberger, 2010). Manyof these studies also looked at consumer be-havior and consumer perceptions in the contextof WTP for coffee labeling.

Pelsmacker et al. (2005) conducted a surveyon 808 Belgian respondents to measure their WTP for fair trade coffee and found that thosewho preferred fair trade coffee (about 40%of surveyed samples) were more idealistic, butsocio-demographically not significantly differ-ent from the average consumer. Their findingsshow that on average Belgian consumers werewilling to pay a 10% premium for coffee with afair trade label. Arnot et al. (2006) also inves-tigated consumers’ purchasing behavior with re-gard to fair trade coffee in Canada and found thatbuyers of fair trade coffee were much less pricesensitive than those who bought conventionalcoffee.

In a study on label performance and con-sumer WTP for fair trade coffee in the UnitedStates and Germany, Basu and Hicks (2008)concluded that consumers’ WTP was positivelyrelated to the scope of the fair trade labelingprogram, but only up to a critical level. Inter-estingly, the results on consumer reaction to-ward fair trade coffee were consistent in the twocountries. Another U.S. example on fair tradecoffee found th at the idea of purchasing abranded fair trade coffee was appealing to onlya small percentage of coffee consumers (Wolfand Romberger, 2010). Furthermore, Wolf andRomberger found that consumers may perceivethe quality of fair trade products to be inferior.Fair trade coffee may be rated lower than conventionally produced coffee of the same brandon the four most popular characteristics: flavor,rich taste, high quality, and price.

Findings from the above studies show thatcertain characteristics, including younger age,female gender, higher education, and high in-come may be positively related to higher WTPfor fair trade coffee (De vitiis et al., 2008). Thesefactors are hypothesized to be consistent withthe characteristics of Chinese consumers whohave newly developed preferences for western-style foo ds. As a result, this res earch offersfurther contribution to the discussion of this newfood trend in China.

Data and Methods

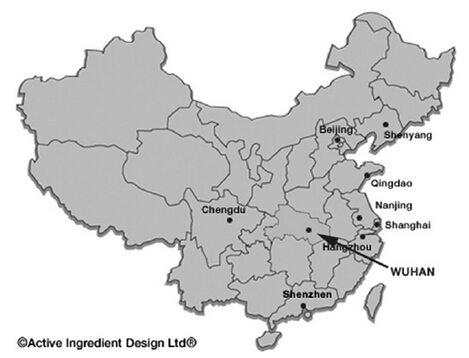

The data used in this analysis were collected bya face-to-face survey in the city of Wuhan inHubei province of China (Figure 1). Wuhan isone of the 10 most populous cities in the Peo-ple’s Republic of China. The city is recognizedas the political, economic, financial, cultural, ed-ucational, and transportation center of centralChina. For many Chinese consumers, coffee isno longer an unknown beverage. Although it maybe possible to examine consumers in cities suchas Beijin g and Shanghai, the consumers who areoften considered as the front-runners setting new consumption trends in China, it will be of moreinterest to understand how a less ‘‘adventurous’’consumer group may respond to coffee. On theother hand, actual coffee consumption may stillbe low for most Chinese consumers, especiallyfor those in remote or largely rural areas. Thus,it will be more descriptive to study consumersin an urban environment. Although many of itsresidents follow c onsumption styles of thosein mega-cities such as Beijing and Shanghai,Wuhan also offers a strong representation of themore interior China, making it an appropriatecandidate for study. Nevertheless, readers arereminded that results of this study are from aspecific city in China and may or may not berepresentative of the entire body of Chineseconsumers.

Figure 1.The map of China and location of Wuhan city (Source: The figure is adapted fromhttp://www.chinaarray.com/yangtze.html)

A total of 564 completed questionnaireswere collected during October and Novemberof 2008. Surveyors were students and facultymembers from a local university in Wuhan.Prior to implementing the survey, the ques-tionnaire was pre-tested to improve clarity andreduce hypothetical bias. Individuals near cof-fee shops and cafe´s were randomly approached.Since instant coffee is still a large componentof the Chinese coffee market and it is mostlysold in grocery stores, the survey group alsorandomly intercepted consumers at grocery stores.To reduce sampling bias, surveys were con-ducted on different days of the week and dif-ferent times of the day. Potential respondentswere first asked whether they would like to par-ticipate in a study about coffee. Generic wordingwas used during this process to ensure that re-spondents would not be encouraged or discour-aged to participate because of the particularproduct being considered. It is worthy to pointout that despite the effort we took to reducesampling bias, caution must be taken when gen-eralizing the results to a larger consumer group.

Not surprisingly, the participation rate amongyounger individuals was significantly higherthan that among the older group (roughly age50 and above). This is consistent with the pro-file of Chinese coffee consumers—a consumergroup mostly composed of young and white-collar individuals (Beijing Zeefer ConsultingLtd., 2009). Besides information about generalcoffee purchasing and consumption behavior and demographic questions, the key variable inthis analysis was the Chinese consumers’ WTPfor fair trade coffee. Each respondent was giventhe price of a regular (non fair trade) mediumcup of coffee of U20. (At the time of the study,U20 was about $3 in U.S. dollars.) The re-spondent was then presented a logo of fair tradecoffee with its definition: ‘‘coffee bearing thislabel means that traders have agreed to pay afair price to marginalized coffee farmers whoare organized in cooperatives around the world,particularly developing countries in Asia, Africa,Latin America, and the Caribbean.’’ The logothat was present ed to resp ondent s was t he of-ficial seal used by the Fair Trade Labeling Or-ganizations Int ernational (Figure 2) an d thedefinition was translated into Chinese.

After allowing respondents to read the infor-mation related to fair trade, a payment cardcontingent valuation question was adopted toelicit consumers’ willingness to pay . In the past,conjoint methods have been used when esti-mating WTP for fair trade products (Basu andHicks, 2008; Pelsmacker et al., 2005). Never-theless, Stevens et al. (2000) concluded that inmany cases, results from a contingent valuation (CV) approach yield consistent interpretationswith those generated by a conjoint analysis and,under certain situations, the conjoint estimatesof WTP could be biased upwards. Thus, thisstudy applies a payment card CV method similarto Hu et al. (2011). It is possible that an attitude-behavior gap may exist, especially for a productthat contains ethical attributes (Greenwald andBanaji, 1995). Such an investigation remains aninteresting future research venue in the contextof fair trade coffee.

Figure 2.International Fair Trade Certifica-tion Mark by the Fair Trade Labeling Organiza-tions International (Source: The figure is adapted from http://www.fairtrade.net/?=361&L=0)

Respondents were asked how much more theywould be willing to pay for a cup of fair tradecoffee (of the same size) above the regular price.The survey presented them with 16 categori esfrom 1: (U0), 2: (U02U0.99; $02$0.14), 3:(U12U1.99; $0.152$0.29), and up to 16: (U14or more; $2.10 or more). Respondents couldmark one category as an indication of theirwillingness to pay. Figure 3 shows the distri-bution of those reported WTP for a cup of fairtrade coffee. About 11% of the res pondentswere not willing to pay anything above zero;in other words, about 89% of the respondentswere willing to pay a price premium for fairtrade coffee. The range for the mode in WTPwas (U12U1.99; $0.152$0.29). And the ma-jority of the respondents were willing to pay lessthan U5.99 ($0.89) above the regular price (U20;$3). In addition to the lo w WTP categories, thatis, U 02U5.99; $02$0.89, both categoriesU102U10.99; $1.52$1.64 and U14 or more;$2.10 or more also received a notable share ofconsumers.

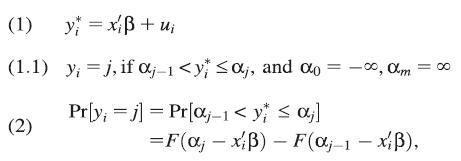

In this case, the choice variable indicatingthe WTP is observed in interval ranges. If y isused to indicate respondents’ discrete choicesof intervals, given x (the explanatory variables),a conventional ordered probit or logit modelcan be estimated. However , Alberini (1995) sug-gested that based on Monte Carlo simulations,an interval-data model is often more efficientthan a discrete choice model. Cameron andHuppert (1991) also outlined the benefit of theinterval-regression specification. The main dif-ference between interval regression and orderedprobit/logit models is the interval regressionassumes known WTP cut points rather than un-known cut points given only by ordinal category indicators.

As in most ordered probit, ordered logit,interval regression, and other models dealingwith ranges, maximum likelihood estimation isemployed. Although the analysis of an ordinaryleast square (OLS) regression would not reflectthe uncertainty concerning the nature of the ex-act WTP va lues within each interval, nor wouldit deal adequately with the left- and right-censoring issues in the tails, it would provide abaseline estimate for rele v a nt parameters. Hence, a linear OLS regression is applied as well. In theOLS model, the dependent variable must be aprecise measured value, so the midpoint of eachinterval category for the given WTP categoriesin the questionnaire is used.

Figure 3.Distribution of Chinese Consumers’ Willingness to Pay (WTP) Price Premium for FairTrade Coffee

Normality is assumed for the interval re-gression. If normality was clearly incorrect, theestimated coefficients would likely differ sig-nificantly between OLS and interval regression.This can serve as an ad hoc check of the nor-mality assumption. The model set-up for orderedprobit/logit is:

where yiis the true latent (or unobserved) WTPknown only to the respondents; values a1, a2,..., aJare unknown boundaries; x are a set ofindependent variables; and b are unknown co-efficients to be estimated. The or der ed logitmodel u has a logistic cdf: F(z) 5 ez/(1 1 ez).For the or dere d probit mode l, F is the standardnormal cdf. In the interv al regression, the modelset-up is similar to Equation (1) except that theinterval boundaries are known: where yiis only observed to lie in the (J 1 1)mutually exclusive intervals (2‘, a1), (a1, a2],...,(aJ, ‘). Given the answers individuals gavein the survey, y * lies in corresponding intervals,that is y* £ 0, 0 < y* £ 0.99, ..., and 14 £ y*.The interval regression is more efficient than anordered probit model, since the estimation pro-cedure uses information on the scale of y*toproduce an estimate of s, instead of requiring sto be normalized to one.Negative WTP suggests that consumers mayrequire compensation to consume fair trade cof-fee. There could be several reasons for this be-havior. For example, consumers may believethat fair trade growers may have hired childrenin the production process, the way fair tradecoffee was produced is not sustainable for theenvironment, or that farmers would not actuallygain from various associations of fair trade.These reasons are plausible, but given wide-spread positive WTP discovered in the relevantliterature, it is reasonable to set the lower boundto zero. The questionnaire does not apply a WTPcategory for less than U0; the amount less thanzero is treated as the zero category. The maxi-mum likelihood estimation is constructed fromterms such as Pr[0 < y* £ 0.99], Pr[1 < y* £1.99], etc., under the assumption of normality of disturbances.

where yiis only observed to lie in the (J 1 1)mutually exclusive intervals (2‘, a1), (a1, a2],...,(aJ, ‘). Given the answers individuals gavein the survey, y * lies in corresponding intervals,that is y* £ 0, 0 < y* £ 0.99, ..., and 14 £ y*.The interval regression is more efficient than anordered probit model, since the estimation pro-cedure uses information on the scale of y*toproduce an estimate of s, instead of requiring sto be normalized to one.Negative WTP suggests that consumers mayrequire compensation to consume fair trade cof-fee. There could be several reasons for this be-havior. For example, consumers may believethat fair trade growers may have hired childrenin the production process, the way fair tradecoffee was produced is not sustainable for theenvironment, or that farmers would not actuallygain from various associations of fair trade.These reasons are plausible, but given wide-spread positive WTP discovered in the relevantliterature, it is reasonable to set the lower boundto zero. The questionnaire does not apply a WTPcategory for less than U0; the amount less thanzero is treated as the zero category. The maxi-mum likelihood estimation is constructed fromterms such as Pr[0 < y* £ 0.99], Pr[1 < y* £1.99], etc., under the assumption of normality of disturbances.

The empirical specification for Equation (1)is:

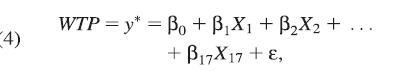

where the dependent variable (WTP)isex-plained by 17 independent variables (Xs), whilethe bsare parameters to be estimated. Theexplanatory variables consist of demographic,consumption, and ethical concern charac ter-istics variables. Robust estimators are used forall four models (OLS regression, interval re-gression, ordered probit, and ordered logit). Thedefinition and statistical summary for each vari-able is shown in Table 2.

The demographic independent variables in-cluded in this study are male, age, income,full_time, size, and marry. The consumptioncharacteristic independent variables included inthis study are bghtcofe, madecofe, buy_cofeshop,flavor, amtcons, five_years, over_ fiveyears,expeccons_in, and expeccons_de. The con-sumption patterns of cof fee consumers capturetheir drinking habits and past coffee purchasingbehaviors. Variables related to drinking habitsare madecofe, flavor, amtcons, five_years, andover_fiveyears; and v ariables related to purchas-ing behaviors are bghtcofe and buy_cofeshop.

Variables describing the length of time as acof fe e consumer, five _yea rs and over_ five years,are both included to examine respondents’ ex-perience on their fair trade coffee willingness topay. During the pre-tests, consumers exhibiteddifficulty recalling the exact number of yearsduring which they have been drinking coffee.As a result, several ranges were used in thesurvey and the two dummy variables reflect therange included in the surv ey. Besides coffee con-sumption habits and purchasing behaviors, we also consider the expectation for future coffeeconsumption, that is, an e xpected increase in cof-fee consumption, expeccons_in, and an expecteddecrease, expeccons_de.

Two variables are used as proxies for con-sumers’ e thical and environmental concerns:prior awareness of free trade and organic coffee,FTknown and org_known. Consumer ethical concern has been greatly discussed by manyprevious studies, and ethical concerns havebeen shown to partially affect respondents’WTP for fair trade coffee. There could bemany different ways to gather this type of in-formation. Our study here simply asked if re-spondents know about fair trade and organicfoods. Although these are not questions de-signed specifically to gauge Chinese consumerethical and environmental concerns, manyissues related to fair trade and organic pro-duction directly involve issues with ethical andenvironmental nature. Thus, we use these twovariables to approximate these concerns con-sumers may have. Future work may expand t hisstudy by explicitly including variables rep-resenting consumer ethical and e nvironmen-tal conc erns on food together with the othervariables in this study. Focusing on drinkinghabits, purchasing behaviors, expectation oncoffee consumption, and ethical/en vironmentalconcerns, these factors do enable us to deter-mine the consumpt ion patterns for Chinese consumers.

After conducting the interval regression,marginal impacts of explanatory variablescan be estimated. Following Cameron andHuppert (1991), the marginal impacts are @WTP/@x. G iven Equat ion (4), the dependent var i-able represents true monetary values. For in-stance, U2toU2.99; $0.32$0.44 meansa specific range of actual prices for willing-ness to pay. Given this nature, the marginalimpacts in the interval regression are actuallymarginal values and can be interpreted simi-larly as in an OLS model. In ordered probitor ordered logit models however, the depen-dent variables are ordinal category indicators;therefore, the coefficients cannot be interpreteddirectly. One way to assis t interpretation is t ocalculate the marginal effects based on theestimated coefficients but these marginal ef-fects do not represent monetary values as-sociated with fair trade coffee willingness topay. On the other hand, although the ob-served interval data do not show the exactWTP for anyone, the average increase or de-crease in WTP is still estimable, and the exactWTP can be estimated for individual or groups of consumers.

Empirical Results and Discussions

As a case study, our results set an example ofhow Chinese consumers may treat and reacttoward fair trade coffee through their willing-ness to pay. Table 2 shows that males com-prised about 59% of the respondents. Only 17%of the respondents were married. About 38% ofthe respondents were employed full-time dur-ing the survey period. One can easily argue thatthe average age (about 24-years-old) of therespondents is too young; however, most coffeeconsumers in China are younger than in othertraditionally coffee-drinking countries. Prelimi-nary pilot studies confirm that individuals over40 years of age are rarely coffee drinkers inChinaandonlyasmallpercentageofcoffeecon-sumers are over 30 years of age.

On average, family size was about threepeople per household in the sample. In addi-tion, about 68% of our respondents had boughta cup of coffee, and 72% had made a cup ofcoffee in the last 30 days before the survey.About 62% of the respondents showed that theywere used to drinking regular black coffee (orblack coffee with only creamer or sugar). Forthe quantity consumed, on average our respon-dents drank about 4.6 small cups of coffee perweek. However, 56% said they had been reg-ular coffee drinkers for up to 5 years, and only9% of the respondents had been regular coffeedrinkers for over 5 years. In terms of futurecoffee consumption, 33% answered they wouldincrease consumption, 10% expected to decreasefuture consumption, and the rest would likelyremain at the same consumption level next year.The survey also included a set of knowledgequestions on how much consumers knew aboutorganic and fair trade coffee. About 45% of therespondents knew at least something about or-ganic coffee, but only about 34% knew relevantinformation about fair trade coffee. This resultshows the potential importance of future producteducation if producers wish to make fair trade(or organic) coffee more visible to the consumers.

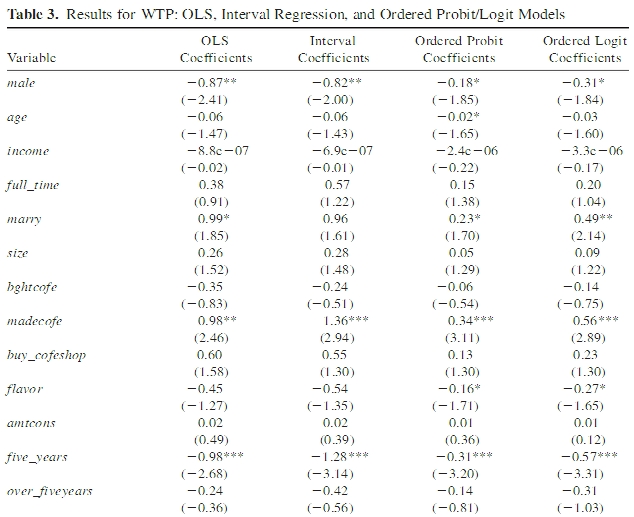

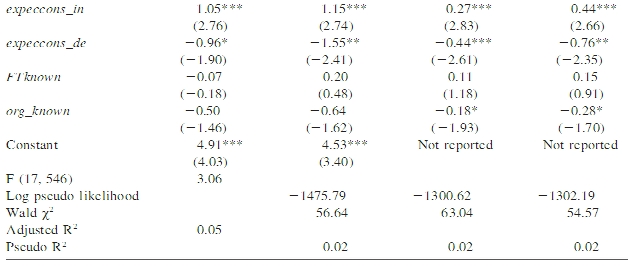

The results of OLS regression, interval re-gression, and ordered probit/logit models forWTP are shown in Table 3. Overall, these fourmodels are well behaved and present consistentestimation results. All but four coefficients were estimated with consistent signs and significancelevels across these models. The four coefficientsare associated with v ariables age, marry, flavor,and org_known. Although variables marry andflavor are significant in the ordered probit/logitmodels, they are mostly marginally significant.

In addition, since the coefficients in these mod-els do not represent monetary values directly,they offer less information in interpretation.The demographic and consumption variablesfor WTP were generally consistent with aprioriexpectations. Results from the OLS and the interval regression resembled each other closelyindicating the assumption of normality was wellmaintained by the data. It is noteworthy that theestimated intercepts of the ordered probit/logitmodels included 15 cut points. They are notreported in Table 3 but are available from thecorresponding author. Since the dependentvariables for ordered probit/logit models wereordinal category indicators, the magnitude of co-efficients in these two models would also bedifferent up to a scal e. Fur the rm ore, due to thenonlinearity of t hese two models, we cannotinterpret the magnitude of the coefficients di-rectly. However, it is still possible to interpret theestimated signs and compare them to the other two models.

Since the interval regression offers the mostintuitive interpretation of the data, the follow-ing discussion is focused on the interval re-gression results. Of the demographic variablesin the interval regression model, only the vari-able male was statistically different from zero atthe 5% significance level. It has a negative sign,implying that female respondents were willingto pay more for fair trade coffee than male re-spondents. This result is consistent with fair tradeproponents among Belgian consumers (Pelsmackeret al., 2005). As compared with female respon-dents, male respondents would like to pay aboutU0.8 ($0.12) less for a medium cup of coffee.The higher WTP by female consumers for fairtrade coffee thus benefiting disadvantaged prod-ucers may be related to the fact that females areoften a disadvantaged group in many societiesin the world whether developing or developed countries.Among variables capturing respondents’ gen-eral cof fee consumption patterns, four variableswere significant (most of which were significantat the 1% le v el) and were consistent across allfour estimated models. These v ariables are made-cofe, five_years, expeccons_in, and expeccons_de.Results for the variable madecofe suggest thatcompared with those who did not make coffeeby themselves, respondents who made coffee bythemselves would be willing to pay about U1.4($0.21) more for a medium cup of fair tradecoffee. This observation may be due to the factthat respondents who made their own coffeecould be in a better p osition to control the quality of their coffee, thus were more willingto pay for the additional ethical attribute of fairtrade, knowing these results could have impor-tant implications for coffee marketers in China.For instance, they may consider concentratingtheir fair trade labeling effort on grocery storecoffee products that will likely be consumedat home, rather than those in coffee shops andrestaurants.

One interesting finding relates to the vari-able five_years. This is a dummy variable indi-cating that the respondents have been a regularcoffee drinker for up to 5 years, while the vari-able over_fiveyears is a dummy variable indi-cating those with a longer than 5-year history asa regular coffee drinker. The result of the vari-able five_yea rs indicates that compared with bothoccasional coffee drinkers (the omitted category)and the long term cof fee drinkers (represen ted byvariable over_fiveyears), respondents who hadregularly drank coffee for up to 5 years werewilling to pay about U1.3 ($0.20) less for a me-dium cup of fair trade coffee. This may suggestthat compared with inexperienced coffee drin-kers—who may still be excited about their newtaste, thus may favor additional features of theircoffee—individuals who have been consumingcoffee for a few years may be more composedand less excited about these fe atures. Yet, forlong-term coffee consumers, their experiencemay enable them to form preferences for featuresthey truly prefer, such as fair trade, in addition tothe price factor.

In regards to future consumption expecta-tions, respondents who would like to increasetheir coffee consumption (variable expeccons_in)would be willing to pay about U1.2 ($0.18) moreof a price premium for a medium cup of fairtrade coffee compared with those who decidedto stay at the same coffee consumption level inthe following year . Howe v er , for those r e sp o n-dents who would like to decrease their cof fee con-sumption (variable expeccons_de )inthefollowingyear, their WTP would be about U1.6 ($0.24)less than those who would remain at the samelevel. The effects of these two variables showthat consumers’ WTP for fair trade coffee isclosely related to the volume of coffee consump-tion. Moreover, the WTP associated with thevariable expeccons_de represents the highest absolute magnitude of WTP measure among allsignificant variables in the interval regressionresult, suggesting that how much coffee con-sumers would like to purchase in the followingyear was likely one of the most important de-terminants on their WTP for fair trade coffee.

None of the variables related to prior knowl-edge, FTknown and org_known, were significantin the interval regression. Since fair trade cof-fee incorporates information that may not befamiliar to everyone, one would expect that ifconsumers were aware of this product, they wouldlikely be will ing to pay more. Similarly, bothorganic and fair trade coffee might be correlatedto ethical and environmentally sustainable con-sumption behavior, and one would expect thatif consumers knew about organic coffee, theywouldbewillingtopaymoreforfairtradecoffeedue to similar ethical/sustainable concerns. Theresult from the interval regression, however, didnot support these hypotheses.

There might be several reasons for this out-come. One of the most important causes couldbe that unlike in many western countries, fairtrade coffee (in fact, even coffee in general) isstill a very new product in China. Many con-sumers may not have formed a well-establishedpurchasing preference for this product and as aresult, their WTP does not necessarily incor-porate all concepts included in fair trade coffee.We expect this result to change over the yearswhen consumers have become more stable intheir preferences. Nevertheless, the fact that themajority of the sampled consumers indicatedpositive WTP for fair trade coffee suggests byitself that ethical consumption may take a siz-eable share of the total demand in the near future.Another reason to support this likely outcomeincludes the fact that China, as a developingcountry, produces many types of products thatcould benefit from the rising domestic and in-ternational consumer support of the notion of fair trade.

Conclusions

This study in v estig ated Chinese consumers’ cof-fee consumption and willingness to pay for fairtrade coffee using a survey implemented inWuhan City, China. The key objective was notjust to ascertain Chinese consumers’ willingnessto pay for fair trade coffee, but also to contributeto the general literature on fair trade productsand to offer grounds for comparison with othercountries, particularly to consumers in westerncountries. Although the i ndependent variablesrelated to ethical and environmental concernswere not significant in this study, many demo-graphic and consumption variables did showsignificant impact to fair trade coffee WTP andwere mostly consistent with previous studies.

Our initial results do recognize that Chineseconsumers are willing to show their appreciationof fair trade coffee through their stated WTP:about 89% of respondents would like to paysome additional amount for a cup of fair tradecoffee above the price of U20 ($3) for a mediumcup of regular coffee. On average, respondentswere willing to pay about U4.5 ($0.68) more fora medium cup of fair trade coffee. This trans-lates into about a 22% price premium. This re-sult is also consistent with Belgian consumersfound in Pelsmacker et al. (2005). Note that anaverage Belgian consumer consumes 10 timesmore coffee than an average Chinese consumer.If Chinese consumers resemble the taste and WTPof Belgian consumers, results not only suggest anexpanding market for the coffee business, buta growing market for fair trade coffee as well.

Data were further analyzed using four dif-ferent econometric models: OLS regression, in-terval regression, and ordered probit/logit models.All models gave consistent results regarding thesigns and significance of coefficients. In termsof factors affecting consumers’ WTP, resultsfound that women would most likely pay pricepremiums for fair trade cof fee. A straightforwardmessage for coffee marketers is to target femaleconsumers to profit through this potentially lu-crativ e niche market. In terms of consumptionhabits, whether the respondent had made a cup ofcoffee in the past, whether they had been a reg-ular coffee drinker, and how they would changetheir cof fee consumption in the following year,all had an important impact on their WTP for fairtrade c offee. Combining with the result thatconsumers’ prior knowledge of fair trade or or-ganic coffee did not have a significant impact ontheir WTP, this study shows that consumers’WTP is more related to their consumption habits.

As pointed out previously, the coffee marketin China is a potentially high growth market,yet there have been no significant studies ad-dressing Chinese consumers’ preference andWTP for coffee. Although coffee, including fairtrade coffee, is not a primary commodity inChina yet, this study gives an idea of how firmscan approach the Chinese coffee market. First,this study shows that like many other countries,fair trade coffee will likely incur a price pre-mium. In addition, Figure 3 shows that not onlywere the majority of consumers willing to payextra for fair trade coffee, there was also a siz-eable portion of consumers willing to pay a sig-nificant premium (U10 ($1.5) or higher) overthe regular price. Coffee marketers should rec-ognize this price premium and adjust theirmarketing strategies to capture the most profit.

Second, the results show that not all consu-mers would be willing to pay the same amountof price premium for fair trade coffee. De-pending on their demographic features and pastexperience with cof fee, consumers may be clas-sified into different groups; each may have adifferent range of willingness to pay. Marketerscan also adopt corresponding marketing strate-gies to focus on the target groups, while relevantpolicy makers can use proper management toolsto facilitate this rapidly expanding market. Anextension of the current study may be to conducta cluster analysis of consumers to determinemarket segmentation.

Finally, the survey sample consisted primar-ily of young adults, who currently make up themajority of coffee consumers in China. As thisyoung generation grows older and has moredisposable income at hand, it will not be diffi-cult to imagine a strong growth in Chinese cof-fee consumption.

[Received September 2010; Accepted August 2011.]

References

Alberini, A. ‘‘Efficiency vs Bias of Willingness-to-Pay Estimates: Bivariate and Interval-DataModel.’’ Journal of Environmental Economicsand Management 29(1995):169–80.

Allison, M. Starbuc ks Thrives in China, Attacked inBeirut, London. 2009. Internet site: http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/html/businesstechnology/2008628258_webstarbucks14.html (AccessedMay 30, 2010).

Arnot, C., P.C. Boxall, and S.B. Cash. ‘‘Do Ethi-cal Consumers Care about Price? A RevealedPreference Analysis of Fair Trade Coffee Pur-chases.’’ Canadian Journal of Agricultural Eco-nomics 5 4(2006):555–65 .

Basu, A.K., and R.L. Hicks. ‘‘Label Performanceand the Willingness to Pay for Fair TradeCoffee: A Cross-National Perspectiv e.’’ In terna-tional Journal of Consumer Studies 32(2008):470–78.

Beijing Zeefer Consulting Ltd. China CoffeeMarket Overview 2009–2010: The Guidancefor Selling Coffee in China. Farmington Hills,MI: The Gale Group, 2009.Bernard, J., and D.

Bernard. ‘‘What is it aboutOrganic Milk? An Experimental Analysis.’’American Journal of Agricultural Economics91(2009):826–36.

Cameron, T.A., and D.D. Huppert. ‘‘ReferendumContingent Valuation Estimates: Sensitivity tothe Assignment of Offered Values.’’ Journal ofthe American Statistical Association 86(1991):910–18.

Caswell, J.A., and D.I. Padberg. ‘‘Toward a MoreComprehensive Theory for Food Labels.’’American Journal of Agricultural Economics74(1992):460–68.

Catturani, I., G. Nocella, D. Romano, an d G.Stefani. ‘‘Segmenting the Italian Coffee Mar-ket: Marketing Opportunities for EconomicAgents Working along the International CoffeeChain.’’ Paper presented at the 12thCongressof the European Associa tion of AgriculturalEconomists, Ghent, Belgium, August 26–29,2008.

Cranfield, J., S. Henson, J. Northey, and O.Masakure. ‘‘An Assessment of ConsumerPreference for Fair Trade Coffee in Toronto andVancouver.’’ Agribusiness 26(2010):307–25.

Curtis, K.R., J.J. McCluskey, and T.I. Wahl.‘‘Consumer Preferences for Western-StyleConvenience Foods in China.’’ China Eco-nomic Review 18(2007):1–14.

Darby, K., M. Batte, S. Ernst, and B. Roe.‘‘Decomposing Local: A Conjoint Analysis ofLocally Produced Foods.’’ American Journal ofAgricultural Economics 90(2008):476–86.

Devitiis, B.D., M. D’Alessio, and O.W. Maietta.‘‘A Comparative Analysis of the PurchaseMotivations of Fair Trade Products: The Impactof Social Capital.’’ Paper presented at theconference of 12thCongress of the European Association of Agricultural Economists, Ghent,Belgium, August 26–29, 2008.

Doane, D. Taking Flight: The Rapid Growth ofEthical Consumerism . London: New Econom-ics Foundation, 2001.

FriedlNet. Analysis: The Chinese Coffee Market.2003. Internet site: http://www.friedlnet.com/news/03031606.html (Accessed January 20,2011).

Galarraga, I., and A. Markandy a. ‘‘EconomicTechniques to Estimate the Demand for Sus-tainable Products: A Case Study for Fair Tradeand Organic Coffee in the United Kingdom.’’Economia Agraria y Recursos Naturals 4(2004):109–34.

Greenwald, A.G., and M.R. Banaji. ‘‘ImplicitSocial Cognition: Attitudes, Self-Esteem, andStereotypes.’’ Psychological Review 102(1995):4–27.

Hu, W., T.A. Woods, S. Bastin, L.J. Cox, and W.You. ‘‘Assessing Consumers’ Willingness toPay for Value-Added Blueberry Products Usinga Payment Card Survey.’’ Journal of Agricul-tural and Applied Economics 43(2011):243–58.

James, D. ‘‘Justice and Java: Coffee in a FairTrade Market.’’ Paper presented at the NorthAmerican Congress on Latin America Reportto the Americas, 34(2000):11–42.

McCluskey, J.J., and M.L. Loureiro. ‘‘ConsumerPreferences and Willingness to Pay for FoodLabeling: A Discussion of Empirical Studies.’’Journal of Food Distribution Research 34(2003):95–102.

Pelsmacker, P.D., L. Driesen, and G. Rayp. ‘‘DoConsumers Care about Ethics? Willingness toPay for Fair-Trade Coffee.’’ The Journal ofConsumer Affairs 39(2005):363–85.

Shaw, D., and I. Clarke. ‘‘Belief Formation inEthical Consumer Groups: An ExploratoryStudy.’’ Marketing Intelligence & Planning17(1999):109–19.

Stevens, T.H., R. Belkner, D. Dennis, D. Kittredge,and C. Willis. ‘‘Comparison of ContingentValuation and Conjoint Analysis in EcosystemManagement.’’ Ecological Economics 32(2000):63–74.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agri-cultural Service. Global Agricultural TradeSystem Online. Internet site: http://www.fas.usda.gov/gats/default.aspx (Accessed May 29,2010).

Watson, J. ‘‘Transnationalism, Localization, andFast Foods in East Asia.’’ Golden Arches East –McDonald’s in East Asia. J. Watson, ed. Stan-ford: CA: Stanford University Press, 1997.

Wolf, M.M., and C.L. Romberger. ‘‘ConsumerAttitudes towards Fair Trade Coffee.’’ PaperPresented at Australian Agricultural and Re-source Economics Society National Confer-ence, Adelaide, Australia, February 10–12,2010.

World Fair Trade Organization. Fair TradeMovement Welcomes Support by the EuropeanCommission to Fair Trade. 2009. Internet site:http://www.wfto.com/index.php?option5com_content&task5view&id5965&Itemid51 (Ac-cessed May 30, 2010).

World Resources Institute. Coffee ConsumptionData. 2007. Internet site: http://earthtrends.wri.org/searchable_db/inde x.php?theme56 (AccessedMay 30, 2010).Follow us on WeChat: aluokecoffee关注我们的公众微信: 阿罗科咖啡

View (13900)